News

Ardmore Banking Advisors Performs Proof of Concept for Climate Credit Risk Concentration Analysis

by Peter Cherpack, Ardmore Executive Vice President of Credit Technology & Board Member

Executive Summary

The Climate Business Problem for Bankers

The impact of climate change on bank credit risk management has become a topic of interest to regulators, audit firms, bank directors and credit risk managers alike. US bank regulators are beginning to outline plans for climate credit risk disclosures and risk management practices for the nation’s largest financial institutions.

Community and Regional banks realize that while there are no national regulatory plans that currently impact them, it is only a matter of time until some kind of new rules trickle down. Additionally, state governments and the SEC are already taking actions relating to climate that could impact activities for publicly held banks of all sizes.

Many Community and Regional bank credit managers are generally wondering how to get started, and how to use readily available resources to better understand their bank’s exposure to climate credit risk.

The Proof of Concept (POC) Overview

With the understanding that Community financial institutions are proactively looking for suggestions and ideas as to how to take a reasonable path to start understanding their potential exposure to climate credit risk, Ardmore Banking Advisors (Ardmore) designed a simple, high-level process to identify potential climate credit risk in community and Regional bank loan portfolios using common credit risk management practices and readily available resources. (Ardmore is a recognized thought leader in credit risk management for Regional and Community financial institutions, including designing and implementing portfolio stress testing solutions since 2008.)

The two key climate risks to be measured are “Acute Physical Risk” (financial impact of severe weather events like hurricanes, wildfires and flooding on the bank’s borrowers and related assets) and “Transition Risk” (the bank’s exposure to loans to borrowers in high carbon footprint industries that will become less valuable as the US turns to more climate friendly and renewable resource alternatives).

In the spring of 2023, Ardmore partnered with a $30 Billion bank to try to identify and track concentrations of loans that were either considered “high risk” to acute physical risks or “high carbon footprint” based on borrower industry.

A key to the success of the initial POC would be to leverage commonly used credit risk management techniques and readily available resources to create meaningful credit risk concentration reporting analysis.

Results of the POC

Working with simple practices like identifying loans by higher carbon industry coding (NAICS Codes) and sourcing publicly available resources such as county code level climate risk scores, Ardmore was able to produce useful and meaningful high-level information about the bank’s exposure to climate related credit risk.

During the process, we also learned more about the perceived difference between physical climate risk and transition climate risk, as well as the importance of using understandable climate risk scoring.

The bottom line is that the process worked, and is a great first step for Community and Regional banks that want to create awareness in their institution of the potential impact of credit risk on their loan portfolios – without a large expenditure of resources. The process also lays the foundation for more sophisticated credit risk practices as appropriate.

Climate Credit Risk – Background

The nation’s financial regulators are now sharing their future expectations for banks related to the growing concern of climate risk. Their particular emphasis is focused on the impact of climate change on an institution’s credit risk. While the near-term direct regulatory impact is currently limited to the country’s largest institutions, there is an understanding that it’s only a matter of time until Community and Regional banks will have to address similar regulatory expectations.

Credit risk managers from banks of all sizes can start this process by understanding which types and levels of climate risk they have in their portfolios, and how to track them going forward. It’s crucial to utilize their baselines of risk appetites with thresholds when looking at emerging risks like climate credit risk.

Once again, there are no proposed regulations or rules relating to managing climate related credit risk for Community banks at this time. However, that does not mean that Community and Regional banks are not interested and concerned about the potential impact of this important emerging area of credit risk. Regulators, auditors, bank directors and risk/credit managers are all beginning to consider how much risk climate may create, and what bank management should be doing to proactively learn about the potential risks to their investors, shareholders and depositors.

Many Community and Regional Banks also realize that with every new risk there are new opportunities, so further research and understanding in this area can be a strategic advantage. There are significant geographical aspects to consider as well. Within the last 12 months we have seen state governments pass climate-related legislation that may impact bank credit practices. The state of Washington is banning sales of new gas cars by 2035, following California. Certainly, at a minimum this would impact auto dealer lending strategies in that footprint. Similarly, continued rising insurance costs in certain regions prone to climate events are one factor that lenders are facing today.

To understand a bank’s potential credit and risk exposure to climate sensitive and carbon sensitive assets and assets threatened by climate events, credit managers need to start with identifying, flagging and reporting loans that are either in geographical areas that are more likely to be impacted by physical climate risks and those that are made to higher carbon industries representing potential transition risk.

Climate Credit Risk Proof of Concept Project Overview

Banking regulatory agencies are now looking at rules intended to disclose how larger banks and other firms are incorporating climate risk into their risk management and overall business framework and strategies. That includes the impact of physical risks, such as the risk of financial losses from acute weather events like hurricanes and wildfires, and transition risk that come from shifting away from certain industries to a low-carbon economy and possibly creating so-called “orphaned assets.” In Europe these new rules are already in place in many countries, and the US government is looking at the European framework as a possible roadmap for the US financial industry.

As in the case with any emerging risk category, a logical first step is to identify higher risk assets (loans) and monitor the bank’s exposure. Once such assets are flagged, an exposure baseline can be set, and equipped with that knowledge credit managers can look at trends, the impact of mitigation strategies and portfolio behavior like roll off and risk rating changes over time.

Banking is an information business, but for most Community and Regional institutions, climate data is not usually collected or tracked for most originations, and there may not be places in credit systems of record to maintain key climate risk attributes. However, even considering those limitations, there are some relatively simple steps bank credit managers can take now with the data and tools they already have to start to be aware of climate credit risk exposure in their portfolios.

The following outlines an approach and case study conducted in the Spring of 2023 to prove the concept that bankers of Community and Regional institutions – with restricted resources – can successfully start a proactive climate credit risk management process within their portfolios.

Monitoring Potential Transition Risk – Identifying High Carbon Industries

A simple and available way to identify high carbon industry exposure is to use standard industry codes, also called “NAICS Codes”, to identify carbon sensitive borrower concentrations and exposures. Some obvious examples include coal, oil, mining, refining and supporting industries like trucking, drilling and refining. Once the “High Carbon NAICS codes” are tagged to loans, credit risk analysts can then look at exposure, trends and concentrations in those loans and establish a current baseline exposure.

Unfortunately, there is no “standard high climate industry list” of NAICS codes available. It would be very difficult for an agency of the US government to designate any borrower or industry to not lend to – so it is up to the bankers and industry groups to create their own lists for carbon sensitivity. Fortunately, there are a number of climate awareness organizations, industry experts and published papers that can be easily found and leveraged as a source for identifying high climate industries. Using a simple online NAICS code look up, industry names can be translated to the codes.

NAICS codes are assigned in a hierarchical manner – with the highest level being a two digit code (like “53” for “Real Estate Rental and Leasing”) then, as the industries get more specific in that more general industry category, the code adds digits to be more specific (like 532412 “Construction, Mining, and Forestry Machinery and Equipment Rental and Leasing”). So, some care must be taken to not choose broader categories of NAICS that may inadvertently include a low carbon sub industry.

In one example, 5-digit NAICS code “22111” represents industries and companies that generate power – an obvious higher carbon category. The next level down reveals that the 222111 category includes both 221115 “Wind Electric Power Generation” and 221112 “Fossil Fuel Electric Power Generation”. To exclude Wind and other lower carbon industry providers like Solar, it is important to look at all of the detailed codes, often down to the six-digit level. It is recommended that each credit manager look closely at the codes in their portfolio and do their best to only tag those borrowers at their most relevant, specific industry level.

It is likely that an “industry best practice” climate transition list will evolve over time that can be shared by credit risk managers. Until then credit managers will have to accept some imprecision in their industry lists and understand a certain level of “directional correctness” in their analysis. Using readily available sources including the SBA, EPA the Bureau of Labor Statistics and industry group research publications from Ceres, JP Morgan Chase and Moody’s, Ardmore constructed its own list in the winter of 2022. This list was shared with the beta bank participating in the POC prior to the start of the project.

Monitoring Physical Climate Risk – Applying Geographical Climate Risk Scores

A relatively simple way to address the risk created by acute climate physical risks in a bank’s portfolio would be to look at loans by primary collateral types like CRE property types. Examples would include hotels, offices or residential loans in riskier geographic areas like shore and waterways, as well as locations more prone to climate incidents like hurricane, wildfire and floods. Studies and statistics already exist that breakdown geo-locations like State, County, SMSA and Zip codes into climate risk categories based off historical conditions and future estimates.

While some of these geo-location climate risk scores are becoming available at significant cost from data and analytics companies, other similar no-cost alternatives exist. In Ardmore’s experience, companies that are anxious to sell their climate risk data are often either offering very detailed data to assist a bank in assessing risk building by building at a transactional level, or are offering very rich in-depth data that includes concepts like building resiliency and projected NOI impact. For the sake of this early effort in identifying potential climate risk, it is Ardmore’s opinion that more detailed climate data is needed as higher level composite climate risk scores are sufficient resources.

One government produced and available climate score is FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI). It contains US county level and census tract physical risk data scores and data that can be downloaded at no cost. It incorporates expected losses from a wide range of physical risks as well as social vulnerability and community resilience to get to an overall risk index. It was designed to help illustrate the United States communities most at risk for 18 natural hazards. It was designed and built by FEMA in close collaboration with various stakeholders and partners in academia; local, state and federal government; and private industry. Risks tracked and built into the score include:

- Avalanche

- Coastal Flooding

- Cold Wave

- Drought

- Earthquake

- Hail

- Winter Weather

- Heat Wave

- Hurricane

- Ice Storm

- Landslide

- Lightning

- Riverine Flooding

- Strong Wind

- Tornado

- Tsunami

- Volcanic Activity

- Volcanic Activity

- Wildfire

In addition to the scores, FEMA has created banding from low to high based on scores:

| NRI Band Description | Min Value | Max Value |

| Very Low | 0 | 48 |

| Relatively Low | 48.00001 | 82.5 |

| Relatively Moderate | 82.50001 | 95.4 |

| Relatively High | 95.40001 | 99.53 |

| Very High | 99.53001 | 99.99999 |

FEMA has exhaustive and very detailed documentation explaining the various calculations that go into the scores. The data available for download is fairly voluminous and detailed, should the banker care to dive deeper into specific vulnerabilities and scoring patterns. For the sake of our POC, Ardmore used the composite rating by county. We did look at the top five “Very High” NRI rating cities/counties by exposure and business line, showing each of the 18 component ratings to illuminate the logic behind the composite scores.

While it appears that the NRI database is a good, accessible source for climate risk geo-scores, just as important are the locations the banks use for associating the scores. Most banks track borrower name and address for ownership information and statement mailings, etc. Unfortunately, in many cases the borrower name and address in the bank’s system of record is not the same as the collateral location – most obviously in the case of commercial real estate collateralized loans. While the borrower name and address may in many cases be “directionally correct” having collateral locations for collateral based loans is much more relevant and valuable for credit risk assessment.

Many banks have collateral management or tracking systems, and these are good resources for actual collateral locations. In the case of this POC, the bank was able to source a collateral location file for their commercial/CRE portfolio loans which was used to associate the specific exposures with the NRI geo-location climate scores. For banks without a collateral location file, gathering locations of the largest CRE loans would be a good place to start shoring up source data for NRI scoring.

Proof of Concept Project Structure

What follows is a brief outline of the steps taken in Ardmore’s “Community and Regional Bank Climate Risk Concentration Analysis Proof of Concept” project started in March of 2023. This outline can be used as an approximate model for similar bank internal efforts:

Resources Used

- Commercial Trial Balance as of 3/31/23 with industry standard credit data fields

- Collateral location file listing loan numbers and primary collateral location by zip code

- Residential loan listing (loan numbers, exposure and outstanding and zip code only)

- Ardmore-created “High Carbon NAICS Listing” file

- 2023 FEMA NRI score database download file

Technologies Leveraged

- SQL database and scripting, reporting (Ardmore’s myCreditInsight proprietary credit database and reporting tool)

- Excel (Downloads, Imports, Analysis)

Reports/Analysis Created

- Concentration report by third-level NAICS (4 digit) showing exposure to high carbon industries

- Concentration reports run showing weighted average NRI codes by portfolio concentration segments (CRE Property Types, third-level NAICS code)

- Concentration reports run using “Very High” NRI Code band, sorted by the same segments

- Concentration reports run using both “Very High” NRI Code bands and “High Carbon” industries with the same segmentation

- A concentration report showing all loans by NRI band, and one each showing CRE loans and Residential by NRI Band

- Concentration reports run using “Very High” NRI Code bands and line of business (CRE, Residential, All Other) by City sorted by Outstanding Balance

- Manually created (Excel) “Top Five” report showing top five cities by business line based on outstanding loan balances, and all 18 NRI score components

Some Key Learning Points from the POC

CRE & Transition Risk Too Obvious

An early takeaway from the results of the POC is that transition risk is much harder for Community and Regional banks to deal with then the physical risk. One high-emission NAICS industry is Real Estate. Real Estate – from Offices to Industrial – even Single Family Residential – are all listed as “high carbon impact”. This means that most of Community bank’s loan portfolios are likely to be immediately flagged as having high carbon impact. Since most Community banks are primarily CRE lenders, this creates a problem for risk analysis from the start.

If the first step in this risk analysis is to elevate risk on a majority of the bank’s loans, the value of the process is lessened in the eyes of bank management; or worse, making the carbon flag appear to be just noise. Ardmore attempted to find more granularity in the Real Estate NAICS codes to see if levels of riskiness could be assigned to subsegments. A representative from the CERES climate consortium shared these comments with Ardmore:

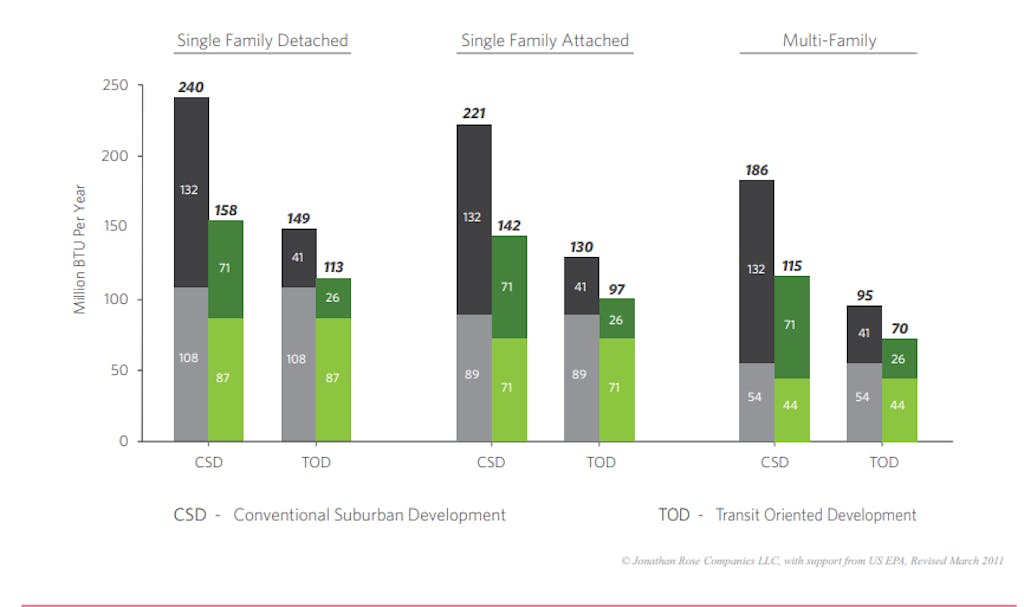

“Multi-family housing is generally less energy intensive since it’s generally smaller spaces (less materials, less energy cost). You can see that on this chart on the first page of the EPA report:

Also, there is a green MBS market out there – again, higher volumes on the multi-family side. It does get difficult to get into these nuances with the NAICS codes – our view is the NAICS codes can be a way to start assessing climate risk but then banks need to engage their clients to really understand and reduce it.”

Considering this context, Ardmore pulled a concentration report of the beta bank’s exposure by CRE property types and found that eliminating the multi-family resulted in a drop of 27% in CRE outstanding – which is significant, but probably not a large enough reduction to be meaningful to bank management.

Moreover, based on this analysis, Ardmore believes that it may make more sense if transition risk (as depicted by the high carbon NAICS codes) and the acute physical risk (as depicted by the NRI scores) is considered and treated completely differently from a risk and concentration management point of view.

Acute physical risks are impacting the bank and their portfolio now, and will increase in the near future. The impact of transition risk is slower and more speculative – and will evolve over a longer timeline, giving banks time to more methodically balance out their higher carbon assets with other new opportunities. As FED Governor Christopher J. Waller remarked in a speech on May 11, 2023: “Transition risks are generally neither near-term nor likely to be material given their slow-moving nature and the ability of economic agents to price transition costs into contracts. There seems to be a consensus that orderly transitions will not pose a risk to financial stability”.

It appears the more urgent issue for most Community and Regional banks to address is the immediate and near-term impact of acute physical risks on a portfolio. On the contrary, some state governments are signing to law bans on high carbon business – like gas powered vehicles, which are 10 or more years away from their final impact, but could start to change banks’ lending practices much sooner.

For Physical Climate Risk Analysis, Good Data is Key

As discussed earlier, to get useful information on physical climate risk there is real value in collateral location data. You will not get meaningful risk data if the owner of an office building on the Florida coast has a home address in Virginia. While many banks have an automating tracking system for collateral location, like the beta bank participating in this POC, reviewing the data provided suggested that in many cases the borrower address on the system is the same as the collateral location. Due to a number of variables, like business and collateral types, this could be accurate – but is more likely not. So, one has to consider that the analysis is directionally correct, but not likely to be extremely accurate.

To increase the likelihood of accuracy, a bank could perform some data validation/clean up – starting with the largest CRE loans. If 75 – 80% if the bank’s exposure can be accurately categorized from the collateral location, that should add to the comfort level with the resulting analysis.

Acute Physical Risk NRI Scores Need Explaining

When the beta bank management was presented with the preliminary results and reports from their physical climate exposure, some of the results did not make immediate sense to the bankers. While the concept of a composite risk score was understood – more specific locations called out as “very high risk” were not intuitive. For example, it was not hard to understand that assets held in Miami Florida were considered “very high risk”. We all saw the pictures of flooded buildings and upside-down boats on roadways during the last hurricane. But what about Chicago and San Diego– which also graded out in the very high NRI bands?

In order to give comfort to the bankers that these results made sense, Ardmore had to dig into the detail of the NRI coding and ranking and show the specific risk drivers that created the “very high” rating.

Further investigation showed that while Chicago is rated moderate to low in many of the more obvious risk indicators (Earthquake, Hurricane, Wildfire and Landslide) it had ratings of relatively high or very high ratings in eight other categories including: Tornados, Extreme Cold and Extreme Heat, Wind, River Flooding and Ice Storms.

In addition, another factor in the composite rating is the NRI “Expected Annual Loss” rating, which was very high for Chicago. This is a calculation that is used to signify the relative amount of dollar value of the physical damage these events create – the density and level of commercial activity comes into play. There is also a “social vulnerability rating” which considers the impact of certain demographic segments of the community that may not be able to readily recover from an acute climate event. Both of these ratings were “very high” for Cook County (Chicago area).

The other example, San Diego, shared in scoring more highly in a few obvious categories (Earthquake, Wildfire, Landslide) but also in some less “top of mind” climate event categories (River Flooding, Heat). San Diego also had a very low rating in “Community Resilience Score” which is an indicator of “the ability of a community to prepare for anticipated natural hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions.”

While these explanations seemed satisfactory enough for the beta bank for the POC, it does suggest that bankers may want to pick and choose ratings that they feel are more important and relevant to loan collectability – than overall community impact from a climate event. Ardmore would suggest that bankers using the NRI rating resource look carefully at the FEMA supplied definitions and explanations of each of the available NRI ratings, and feel free to customize the elements used in their own climate impact analysis.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Yes, Community & Regional Banks Can Do It Themselves, Today

First and foremost, the POC proved that Community and Regional banks can do basic climate credit risk concentration analysis themselves today, with readily available resources. A credit department in a Community bank with some assistance and a few other bank resources can typically add transition and physical risk indicators to their loan data, enabling some basic concentration reporting for a baseline view of climate credit risk in their portfolios.

All banks can perform this type of exercise using Excel, while others may choose to add indicators to their system of record (“Core”) in user defined fields for categorization and tracking. By leveraging the system of record, the institution can usually use Core provided reporting tools for basic analytical reporting.

Larger Community and Regional Banks usually have more IT resources available to either set up or modify existing credit data marts and databases for reporting without major effort. End-user accessible query or report writer tools should be sufficient for this high-level analysis.

At this point, the evolution of climate credit risk analysis for Community and Regional banks as explored in this POC is pretty simple, without precision or sophisticated modeling. While the results may only be high level and “directionally correct” they are still an important first step, and valuable to help the bank understand climate risk in their portfolios.

Climate Credit Concentration Reports can be effective in Raising Awareness and Creating some Tangible Results for Consideration

The results of this type of early high-level analysis are something that can be shown to auditors, regulators and the Board to show evidence of proactive credit risk management of areas of emerging risk. Alerting bank management to the bank’s exposure to climate in the short term (acute physical climate risk events) and longer term (high carbon industries) starts that process.

At this point, most US banks consider climate credit risk to be “just another type of risk” and, as such, all types of risk need to identified, measured and monitored. Starting off by creating risk concentration reporting is a typical first step in all types of credit risk management. Using Excel or a simple database, credit managers can look at this emerging risk through various lenses to gain insights to potential future risk, and possible future controls.

Most important at this point is to demonstrate awareness of this important emerging risk, and show regulatory and other stakeholders that the bank is being proactive in this area. As we all know, it is always better to be ahead of the examiners and external auditors’ expectations than to be told to do something prescriptively by them.

Transition Risk and Physical Climate Risk Are Different

While both types of climate risk can be modeled and analyzed, their nature is very different. Acute physical climate risk is already known to lenders and credit managers today. Flood insurance and other environmental concerns are often considered as a part of making deals. What has changed is both the severity and the frequency of these events – and that appears to only be increasing over time. A new awareness to less typical environmental risks like drought, heat, and sea level change also has to be considered.

Transition risk is considered a little more “fuzzy” by most US bankers today – as the impact is typically more distant and slower to emerge. Most banker see statements about reduced exposure to high carbon and other climate related industries as a problem in 25 years or more – which pales in comparison to meeting the next quarter’s revenue goals.

Due to likely longer timelines for adjusting lending patterns, portfolio mix and risk appetite, fewer Community and Regional US bank credit managers show high concern over the transition risk today. The imprecision of using grouped industry coding like NAICS and the lack of an industry standard for identifying higher climate risk industries and borrowers adds to the uncertainty.

While these issues are valid, the situation is fluid and state and national government priorities are changing. States like California and Washington are banning gasoline engine vehicles in about 10 years, and a major weather event could trigger legislative action like a “carbon tax” more quickly than expected. Having awareness of these risks in your portfolio is still valuable, while perhaps not an immediate focus.

Measuring Climate Risk and Climate Credit Risk are Related, But May Not Be the Same

Using readily available geographical based climate risk scores (like the NRI used in this POC) may include factors not typically included in transactional credit risk analysis. The NRI ratings includes factors like:

- Social Vulnerability Rating – “Social vulnerability is a consequence enhancing risk component and community risk factor that represents the susceptibility of social groups to the adverse impacts of natural hazards, including disproportionate death, injury, loss, or disruption of livelihood.”

- Community Resilience Rating – “Community Resilience is a consequence reduction risk component and community risk factor that represents the ability of a community to prepare for anticipated natural hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions.”

These and other calculations that make up the NRI may not be considered by bank credit and lending staff as significant as these factors influence the overall NRI score. Fortunately, FEMA does include a number of “sub-calculations” or calculation components that after study, bankers may choose to ignore or subtract from the scoring. Unfortunately, this type of analysis adds time and complexity to the process.

Based on reaction to the POC by the beta bank, further explanation of the NRI ratings were required regardless, so deeper analysis of the ratings, or selectively reducing the impact of “social factors” may help in adoption of these types of climate scoring systems.

Possible Next Steps – Climate Portfolio Stress Testing

While this first climate credit risk POC focused on identifying and tracking borrowers and loans that represent elevated climate related credit risk, as discussed earlier, this is only a first step in this evolving process.

Once climate risky loans are properly identified and tracked, more advanced credit risk management practices can be attempted. One obvious “credit management best practice” is portfolio stress testing – or “shocking the portfolio”. This practice is now common place in most banks regardless of size and has proven to be a useful tool to help credit managers anticipate vulnerabilities in their portfolio during changing economic times. This type of stress testing is an expectation of examiners for higher risk all types of portfolio segments today.

Bankers will need to collect and archive some key financial ratios for these types of loans – many of which are CRE, and are already similarly analyzed today. But due to the considerations of industry transition risks other financials will need to be collected for concentration risk stress testing for C & I and other corporate lending. Fortunately, bankers have more time for this longer-term analysis, but data collection is also a long-term process. It is possible that the recent CECL accounting rule, implemented over the past couple of years, may include the collection and storage of this type of data. That avenue should be explored as well.

It is advised that banks of all sizes begin to collect and store key financial ratios and credit risk factors for all loans in their portfolios, to enable climate credit risk stress testing in the next year or two. Climate credit risk is an evolving practice in banking today for all banks, and a common-sense approach using readily accessible resources is a great way to start in 2023. Other more advanced methods and practices are likely to be established by the largest banks, and will trickle down to the smaller institutions over time.

There is an opportunity to be proactive now, and address this area of emerging credit risk, and there is no reason to ignore it, just as overreaction may not be a prudent use of resources for Community and Regional banks today.

- Ardmore Summarizes New SEC Rule on Climate-Related Disclosures

- Ardmore Founder Sandy Spratt Published by Bank Director – 10 Mistakes to Avoid in M&A Portfolio Due Diligence

- The State of M&A in 2024 – A Discussion With Bank President Brian W. Jones

- Case-Study: Testing Climate-Related Credit Risk with Real Earthquake Scenario

- Key Takeaways from Risk Management Association’s 2023 Annual Conference